Early in 1973, two of my brothers and myself were given the job of painting an upstairs bedroom in our house. Once we got past the usual hem-hawing and protestations of having to expend valuable time engaged in such an onerous task, we settled in for an afternoon of slinging paint against the wall and ceiling with carefree abandon. To keep us entertained in our labors, an inexpensive radio was plugged in and my brother found his way on the dial to a station featuring the then new format of “oldies” culled from the nascent days of rock and roll’s beginning (1955-1962). At some point, after hearing an assortment of songs about a book of love, a young guitar wizard, hound dogs, sock hops and “rockin’ around the clock,” a song—a sound—came on, leapt out of the radio and just smacked me up side of the head. The disc jockey intoned “that was ‘Cathy’s Clown’ by the Everly Brothers” at the tune’s conclusion and I would soon be combing the bins at a local record store in search of the 45.

At the tender age of fifteen, I had only the vaguest awareness of the Everly Brothers. My parents, having come of age in the 1930s, had generally disavowed the entire rock and roll phenomenon preferring the sanitized, sedate and (to my tastes) soporific fare provided by Lawrence Welk and his gang. Save for my eldest sister, who had been a teenager at the time Elvis, Chuck Berry, Little Richard and others transformed popular music (but had married and left the household when I was six-years-old), my other elder siblings all came of age in the 60’s and I had been weaned on their music. Unbeknownst to me, my heroes of the day (Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel) were in essence, the musical progeny of Phil and Don. As I would later discover, so many of the popular musical artists of the 60’s and 70’s (e.g., the Beatles, Beach Boys, Mamas & Papas, CSNY, just to scratch the surface) had been greatly influenced by the brothers. Even musicians whose work seemingly bore no relationship to the Everly’s sound, have cited the brothers as having been inspirational (Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Brian May, Steven Tyler, etc.) and/or worthy of great admiration.

In his recently published autobiography (Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life), Graham Nash writes of his and Alan Clarke’s first time hearing the Everly Brothers in the spring of 1957 when they were 15-years-old:

“We got halfway across the floor and ‘Bye Bye Love’ by The Everly Brothers came on — and it stopped us in our tracks. We [Nash & Clarke] sang together, so we knew what two-part harmony was, but this sounded so unbelievably beautiful. … Ever since that day, I decided that whatever music I was going to make in the future, I wanted it to affect people the same way The Everly Brothers’ music affected me on that Saturday night.”

While certainly smitten and intrigued upon hearing Cathy’s Clown, it took several years for my interest and appreciation of the brothers abilities to morph into true fandom (or fanaticism as my wife might attest). Of course, shortly after the Everly’s appeared on my radar, they split-up (in July of 1973) following an infamous incident wherein Phil, during a concert, smashed his guitar and walked off stage leaving Don to inform the crowd, “the Everly Brothers died ten years ago.” Hence, in those pre-internet days, news of what the brothers were doing was scarce and hard to obtain.

In the spring of 1980, I had joined with a fellow Cleveland Institute of Art student in an informal musical partnership that led rather unexpectedly, in a few short weeks time, to a gig—my first!—in front of several hundred students at his high school alma mater. Our repertoire (naturally) drew heavily upon 60’s/70’s artists known for either two or three-part harmony (Seals & Crofts, Loggins & Messina, America, etc.). While our “blend” was not unpleasing, it had taken many rehearsals to achieve some semblance of competence in singing two-part harmonies.

Concurrently, via a local used record store, I had acquired—on a whim for $1.00—an album the Everlys had released in 1965 (Beat & Soul) when the Beatles and other British artists were dominating the charts and the Everlys were descending to “has been” status in the American public’s perception. (Ironically, of course, the Everlys remained wildly popular in Great Britain and other parts of the world.) Hearing their transcendent cover of Mickey & Sylvia’s Love is Strange when I first spun the disc back at my apartment was a revelation. Not the least because, as the liner notes indicated, the entire album had been recorded in the course of two days time. I was aware, with the advent and development of multi-track recording in the mid/late sixties, records by major artists were rarely cranked out with such expediency. Years later I learned virtually all of the recordings Phil and Don made from 1957 to 1966 were recorded “live” in the studio without overdubs. I also learned, to my ongoing astonishment, the brothers seldom rehearsed tunes before recording them.

* * * *

In the wake of Phil Everly’s passing on January 4th, reams of news items and commentary have dwelt almost exclusively on the frequently less-than-cordial and often acrimonious personal relationship between the brothers with multitudinous variations of the “on stage harmony/off-stage disharmony” theme utilized. I’ve no doubt the brothers were not necessarily the best of friends. However, I’d rather remember their art: the recordings and songs they wrote/composed—the legacy of which will undoubtedly continue on for many, many years.

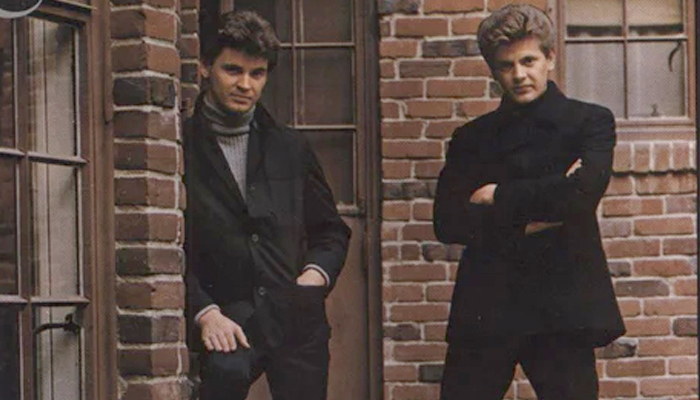

My primary interest and affection for the Everly Brothers has always been in the timbre of their voices. Both were high tenors with Phil’s voice seemingly pitched a perfect third above Don’s. The unparalleled and preternatural beauty of their blend still enthralls when I listen to their recordings. I so admire their consummate abilities as singers/interpreters of songs. Phil’s ability to match Don not only in phrasing, but in dynamics—when Don soars, Phil soars—set them apart from virtually anyone who’s ever sung two-part harmonies. As many have noted over the years, there were times when their blend was so perfect a third voice, a “ghost” harmonic or overtone, could be heard.

I was fortunate enough to hear the Everlys in concert on each occasion they passed through Northeast Ohio in the years following their 1983 Albert Hall reunion. They were consummate professionals, never failing to deliver a great show. I’ve read interviews with Warren Zevon, who had performed with the brothers in the early 70’s prior to their split, where he recounted how they would go from playing to an enthusiastic sell-out crowd of 12,000 people at the Albert Hall in London one week to playing for 300 disinterested people at an oyster bar in North Carolina the following week with the Everlys delivering a great show in each instance. As someone who has performed in numerous venues for less than receptive audiences, I know how extraordinarily difficult it can be not to devolve to a lackadaisical standard of presentation in such circumstances.

Of those various concerts, a particularly cherished memory was seeing/hearing the Everlys (with opening act Dion) in May of 1992 at the Ohio Theater in Cleveland from the vantage point of a dead-center, 2nd-row seat. I also had the opportunity to “meet” Phil and Don after a concert at the Tangiers nightclub in Akron in August of 1990. Alas, since I was too awestruck to speak and had nothing for them to autograph, my interaction with them consisted of me standing awkwardly by while they signed an album for another fan before hurrying off to their tour bus.

However, the zenith and culmination of my concert-going experiences was reached on October 20, 2003 when the Alpha and Omega of my musical universe (Simon & Garfunkel and the Everlys) appeared together at the Quicken Loans arena in Cleveland. At the ages of 64 and 66 respectively, Phil and Don were just beginning to show signs of diminution in their vocal prowess. When they struck the opening chord of All I Have To Do is Dream and sang “dre–ee–ee–ee-eam,” magic filled the air: their two perfectly matched voices, even if somewhat frayed at the edges, could still induce spine-tingling chills.